Mobile System Design Guide

21 October 2024

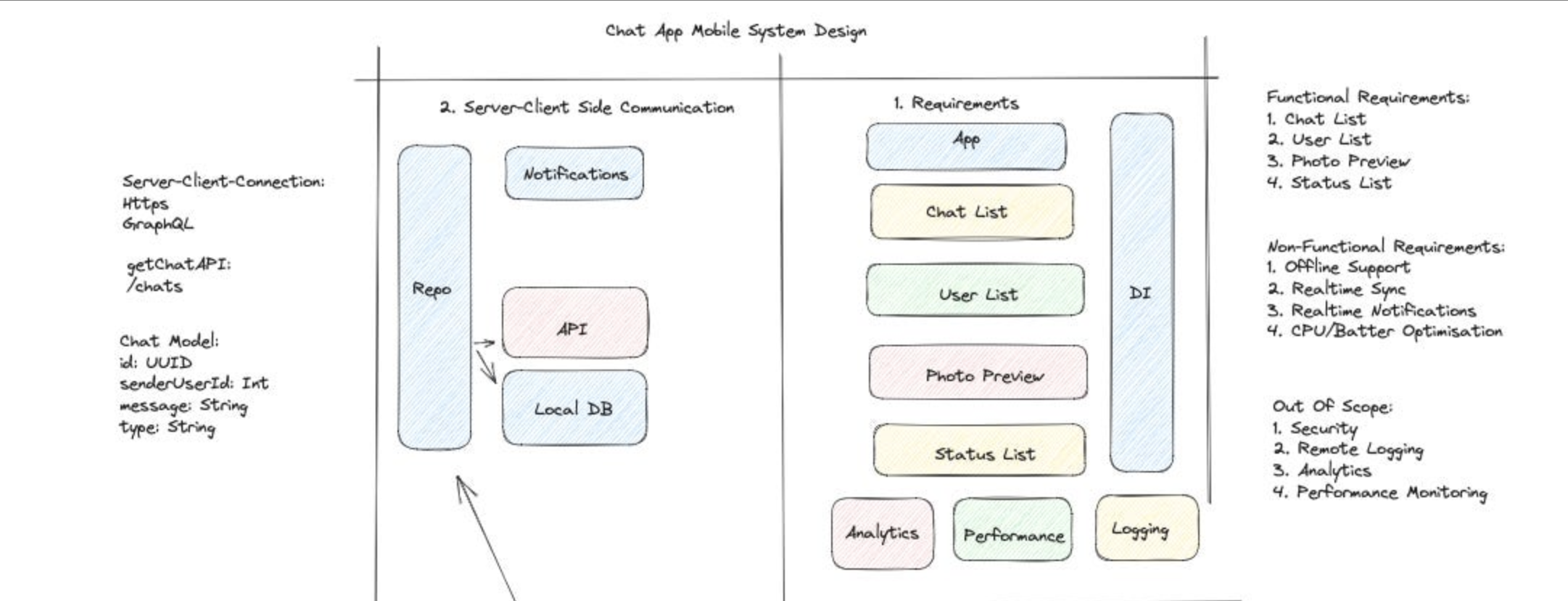

Before building a product, we need to set some requirements, architecture designs, security concerns — all of that. These play an important role in organizing, creating fast and scalable applications. A typical mobile system design interview covers application features, architecture decisions, data modeling, API contracts, and out-of-scope concerns like crash reporting and analytics. I’ve been through enough of these rounds — both as a candidate and on the other side — to know that most people lose points not because they lack technical knowledge, but because they don’t structure their approach well.

I’ve seen candidates burn 5–6 minutes just on their introduction. Keep it short: “I’m X, working on Android applications and libraries since 2020. For the past 2 years, I’ve been leading a team building a messaging product.” That’s it. A typical system design interview runs 40–45 minutes. You need every minute for the actual design work, not your life story.

How to Approach the Interview

Here’s the thing about mobile system design interviews — they’re testing your thought process, not your ability to recite architecture patterns. The interviewer wants to see how you break down ambiguity, make decisions under constraints, and communicate tradeoffs. I’d split the 40–45 minutes roughly like this: 5 minutes for requirements gathering, 15–20 minutes for high-level design, and 15–20 minutes for the deep dive into low-level design.

Communication matters more than most people think. Talk through your reasoning out loud. Don’t just say “I’d use WebSocket here” — explain why. “We need real-time message delivery with low latency, so HTTP polling would waste bandwidth and introduce delay. WebSocket gives us a persistent bidirectional connection, which fits this use case.” That’s what separates a senior candidate from a mid-level one. The biggest mistakes I see are jumping straight into low-level details without establishing requirements, designing in silence for minutes at a time, and trying to cover everything instead of going deep on the things that matter.

Requirements Gathering

After the introduction, start with requirements gathering by asking questions. But be careful — don’t ask for solutions. Ask for constraints and then propose solutions yourself. The interviewer wants to see your thought process, not hear you ask “should I use MVVM or MVI?” Information gathering breaks down into four areas: functional requirements, non-functional requirements, out-of-scope items, and resource constraints.

Functional Requirements

These are the features directly visible to the user. Say you’re designing a messaging app — your functional requirements might look like:

- User can scroll through a conversation list

- User can send and receive text messages in real-time

- User can send attachments and photos

- User can delete or edit a sent message

- User sees read receipts and typing indicators

Now compare that to a food delivery app, where functional requirements shift entirely:

- User can browse restaurants by location and cuisine

- User can add items to cart and customize orders

- User can track delivery in real-time on a map

- User can rate and review past orders

The key insight here is that functional requirements drive your entire architecture. A messaging app with real-time sync needs a fundamentally different networking layer than a food delivery app that mostly does request-response with occasional location updates.

Non-Functional Requirements

These are the qualities that make the app reliable and performant. They’re not features the user directly interacts with, but they feel the absence of them immediately:

- Offline support — Can the user do anything without internet?

- Real-time sync — How fresh does the data need to be?

- Low latency — Is sub-second response time critical?

- Battery optimization — Are we running background services?

- Scalability — How does the client handle 10K messages vs 100K messages?

Resource Constraints

Don’t skip these. Ask about team size — building for a 3-person team vs a 50-person team changes whether you modularize aggressively or keep things simple. Ask about target regions — if you’re targeting areas with spotty internet like rural India, you need an offline-first architecture with minimal API calls. Ask about user volume — millions of concurrent users means your API pagination and caching strategy become critical.

High-Level Architecture

Before jumping in, I always ask the interviewer: “Should I start with the high-level design?” This signals structure in your thinking. High-level design is about the big picture — modules, their responsibilities, and how they communicate.

Client Architecture

For the client side, I almost always reach for MVI (Model-View-Intent) these days. MVVM with LiveData was the standard for years, and it works fine, but MVI gives you unidirectional data flow, which makes state management predictable and debugging much easier. The View emits intents, the ViewModel processes them through a reducer, and a single state object drives the UI. In a messaging app, your state might look like this:

data class ChatScreenState(

val messages: List<MessageItem> = emptyList(),

val isLoading: Boolean = false,

val error: ErrorType? = null,

val isUserTyping: Boolean = false,

val hasMoreMessages: Boolean = true

)

sealed interface ChatIntent {

data class SendMessage(val text: String) : ChatIntent

data class LoadMore(val beforeMessageId: String) : ChatIntent

data class DeleteMessage(val messageId: String) : ChatIntent

data object RetryConnection : ChatIntent

}

The reason I prefer this over exposing multiple LiveData or StateFlow streams is simple — with a single state object, you never end up with inconsistent UI where the loading spinner is showing but the error message is also visible. One state, one truth.

Networking Layer

Your choice of client-server communication depends entirely on the use case. REST over HTTPS works for most request-response patterns — fetching a restaurant list, placing an order, updating a profile. WebSocket is the right call when you need persistent bidirectional communication — chat messages, typing indicators, live location tracking. Server-Sent Events (SSE) fits when the server needs to push updates but the client doesn’t need to send data back frequently — think notification feeds or live score updates. HTTP polling is almost never the right answer for mobile — it wastes battery, bandwidth, and server resources.

Caching Strategy

IMO this is where most candidates fall short. You need to articulate a clear caching strategy, not just say “I’ll use Room.” Think about it in layers: network cache (OkHttp’s built-in cache with Cache-Control headers for static resources), database cache (Room for structured data that needs to survive process death), and in-memory cache (a simple LRU map for things like user profiles that are accessed frequently within a session). The real question is always: what’s your source of truth? For an offline-first app, the local database is your source of truth, and the network is just a sync mechanism.

Data Model Design

This is where you define what your entities look like and how they relate to each other. On the client side, I almost always use Room (SQLite under the hood) because it gives you compile-time query verification, Flow/coroutines integration, and handles relationships well enough for most mobile use cases.

@Entity(tableName = "messages")

data class MessageEntity(

@PrimaryKey val messageId: String,

val conversationId: String,

val senderId: String,

val content: String,

val timestamp: Long,

val status: MessageStatus, // SENT, DELIVERED, READ, FAILED

val isEdited: Boolean = false,

val localUri: String? = null // for attachments not yet uploaded

)

@Entity(tableName = "conversations")

data class ConversationEntity(

@PrimaryKey val conversationId: String,

val title: String?,

val lastMessagePreview: String?,

val lastMessageTimestamp: Long,

val unreadCount: Int = 0

)

Here’s a real tradeoff worth discussing: normalization vs denormalization. In a traditional SQL approach, you’d keep lastMessagePreview only in the messages table and join when needed. But on mobile, joins are expensive when you’re scrolling through a conversation list with hundreds of items. I denormalize lastMessagePreview and lastMessageTimestamp into the conversation entity because the conversation list screen needs to render fast, and duplicating a few strings is a tiny storage cost compared to running a join query on every scroll. The tradeoff is that you need to update two tables when a new message arrives, but that’s a write-time cost you pay once vs a read-time cost you’d pay on every frame.

API Design

For most mobile apps, REST is still the pragmatic choice. It’s well-understood, has great tooling (Retrofit, OkHttp), and the ecosystem is mature. GraphQL shines when your screens need data from multiple resources in a single request — imagine a profile screen that needs user info, recent posts, follower count, and mutual friends. With REST, that’s 4 API calls. With GraphQL, it’s one. But GraphQL adds client-side complexity (Apollo client, cache normalization, schema management), so I’d only reach for it if you’re genuinely dealing with complex, deeply nested data requirements.

Pagination Strategy

This comes up in every system design interview. Two main approaches — offset-based and cursor-based. Offset pagination (/messages?page=2&limit=20) is simple but breaks when items are inserted or deleted between page loads — you get duplicates or skip items. Cursor-based pagination (/messages?after=msg_abc123&limit=20) uses a pointer to the last item you received. It’s stable even when data changes, which is why every real-time app (chat, social feeds, notifications) should use cursor-based pagination.

data class PaginatedResponse<T>(

val data: List<T>,

val nextCursor: String?,

val hasMore: Boolean

)

// API interface

interface ChatApi {

@GET("conversations/{id}/messages")

suspend fun getMessages(

@Path("id") conversationId: String,

@Query("after") cursor: String? = null,

@Query("limit") limit: Int = 30

): PaginatedResponse<MessageDto>

}

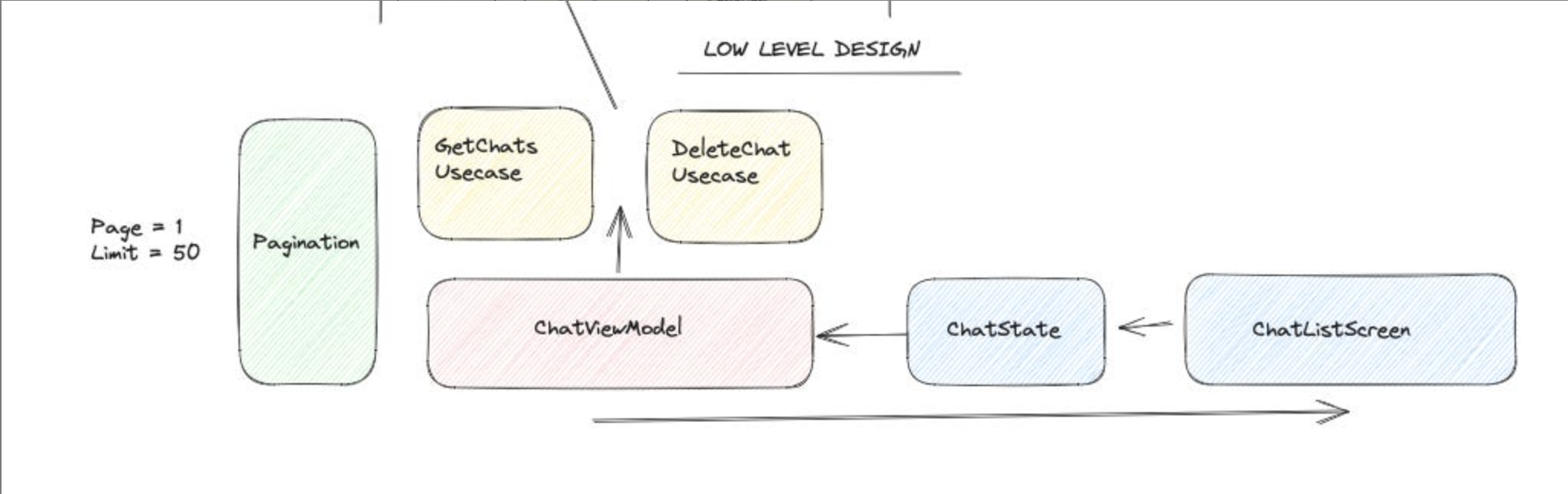

Client Architecture Deep Dive

Now we get into the low-level design. This is where you show the interviewer you can actually build this thing, not just draw boxes on a whiteboard.

Module Structure and Dependency Injection

For a mid-to-large app, I’d structure modules by feature with shared core modules: :core:network, :core:database, :core:ui, :feature:chat, :feature:conversations, :feature:profile. Each feature module depends on core modules but never on other feature modules — this enforces clean boundaries and makes parallel development possible. Hilt is my go-to for dependency injection because it’s built on Dagger (compile-time, no reflection) but removes most of the boilerplate. You define your singletons in the app module, scoped dependencies in feature modules, and Hilt handles the rest.

State Management and Navigation

Each screen gets a ViewModel that exposes a single StateFlow<ScreenState> and accepts intents. The UI layer collects the state and renders — that’s it. No business logic in the Activity or Fragment. For navigation, Jetpack Navigation with type-safe arguments works well enough. The key is keeping navigation events in the ViewModel as one-shot events using a Channel rather than putting them in the state object, because navigation should happen once, not recompose every time state changes.

Deep Dives — The Hard Parts

Offline-First and Caching

An offline-first pattern means every user action writes to the local database first, then syncs to the server in the background. When the user sends a message, it immediately appears in the UI with a “sending” status. A background coroutine picks it up, sends it to the server, and updates the status to “sent” or “failed.” This gives instant feedback regardless of network conditions. For cache invalidation, I use a timestamp-based approach — store the last sync time per data type, and on the next sync, fetch only items modified after that timestamp. It’s simpler than version vectors and works well for most mobile apps.

Sync and Conflict Resolution

Here’s where it gets tricky. When two clients modify the same data offline — say, both users edit a group conversation name — you need a conflict resolution strategy. Last-write-wins is the simplest: whoever syncs last overwrites the other. It’s lossy but acceptable for most non-critical data. For important data like messages, you avoid conflicts entirely because messages are append-only — you don’t edit another user’s message. Optimistic updates are essential for good UX. Update the UI immediately, send the request in the background, and roll back if it fails. The user sees instant response 99% of the time, and the rare failure case shows a clean error state.

Pagination with Paging 3

Android’s Paging 3 library handles the heavy lifting of paginated data loading. The RemoteMediator pattern is exactly what you need for an offline-first paginated list — it loads data from the network into Room, and the UI observes Room via a PagingSource. When the user scrolls near the end, Paging 3 triggers the RemoteMediator to fetch the next page from the network, insert it into Room, and the PagingSource automatically picks up the changes. The beauty of this approach is that your UI always reads from Room, so offline mode is free — you just don’t fetch from the network, and whatever’s in the database is what the user sees.

Putting It All Together — Designing a Chat App

To tie everything together, here’s how I’d walk through a chat app design in an actual interview. Start with requirements: real-time messaging, conversation list, media attachments, offline support, read receipts. For architecture, go with MVI + Repository pattern with Room as the source of truth and WebSocket for real-time message delivery. The conversation list uses Paging 3 with RemoteMediator for paginated loading from the server into Room. Individual chat screens maintain a WebSocket connection for live messages and fall back to REST polling if the socket drops. Messages are stored locally first with a “pending” status, then a SyncWorker using WorkManager picks them up and sends them to the server — this handles cases where the user sends a message and immediately kills the app. For the data layer, cursor-based pagination on the API, Room entities with indices on conversationId and timestamp for fast queries, and an in-memory cache for active conversation metadata. The conflict resolution is simple — messages are append-only, conversation metadata uses last-write-wins, and the server is the ultimate arbiter of message ordering via server-assigned timestamps.

And here we are done! Thanks for reading!